For more than 20 years, London-based RN Aaron Clark has dedicated himself to helping people struggling with mental illness and addiction, but lately he’s felt a sense of hopelessness. He sees too many people falling through the cracks of Ontario’s health system, even though he’s trying his best to keep people alive while advocating for long overdue changes.

Working part time on a community outreach and support team (COAST), Clark begins his day early. He needs to get a jumpstart on his day by reviewing referrals sent to the COAST team from community partners and checking the phone line for calls from people looking to COAST for mental health support and intervention. In this case, support and intervention means helping to avert a hospitalization or preventing further trouble with the law.

The majority of his day is spent joining police partners in ride-alongs to offer care and resources to individuals in the community, some of who may be using substances in public or suffering from other mental health issues. “(Police officers) will point out people who are suspected of using (illegal substances) out in the open and will often say ‘that would’ve been an investigation and possible arrest five or 10 years ago,’” but now in partnership with health providers like Clark, they respond to individuals living with mental illness or addiction using a different approach – proactive crisis interventions, referral to community supports and advocacy when needed.

Although COAST is a new program, Clark says its impact is already being felt.

“There’s been a real shift, at least in our local police services, from looking at addiction from a legal perspective to thinking of it as a health issue, which is something…I’ve personally advocated for a long, long time,” says Clark, who also works full time on an assertive community treatment team, providing long-term support to people with mental health and addiction issues.

But this is just one small step to address the overarching opioid overdose crisis. Nurses across the province who provide care to individuals who use substances recognize that transformative change is needed to ensure the crisis is treated strictly as a health matter.

“We really need to see uptake in the health-care system to increase services and develop supports for people who are experiencing addiction issues,” adds Clark. The province’s current approach to caring for people who use substances falls short and costs lives.

Policies that fall short have real-life consequences. RN Kathy Moreland lost her 18-year-old son Austin Layte to an accidental drug overdose caused by fentanyl poisoning in June 2020. “He just graduated high school and was having pizza with his girlfriend who was still using (drugs) and he thought ‘she’s here with me. I won’t die,’ but they both fell asleep and he died,” Moreland shares. Her story highlights a tragic detail: Just a single encounter with the toxic drug supply can be lethal. Layte’s 16-year-old girlfriend also died two weeks later from fentanyl poisoning.

In 2021, 2,907 people died in Ontario from an opioid-related overdose – a staggering 85 per cent increase over pre-pandemic levels (complete data for 2022 is not yet available). The presence of fentanyl within opioids contributed to 89.1 per cent of the deaths, demonstrating the dangers associated with the toxic drug supply and the need to increase access to safer supply and drug testing. (Data source: Public Health Ontario)

“Nobody can go to treatment if they’re dead,” says Moreland. “The drug supply right now is so poisonous, that every time someone uses, even if they’re with someone or they have naloxone with them, they risk dying.”

Following her son’s death, Moreland has dedicated herself to advocacy through RNAO as president of Waterloo Chapter and through Moms Stop the Harm, a network of Canadian families with lived experience who advocate for policy changes at all levels to end substance use-related stigma, harm and death.

“If he had to die, I have to believe there is a purpose,” shares Moreland. “To know I might save other people from going through this is the only thing I can find that makes it worth it.”

Moreland is not alone in her efforts. RN Louise Lemieux White co-founded Families for Addiction Recovery (FAR) after helping her daughter recover from struggles with both mental illness and substance use disorder. “She was in complete emotional pain and despite seeking many, many supports, she found what worked best for her and that was drugs.”

At FAR, volunteers with lived experience educate “anyone and everyone” about substance use (whether nurses, doctors, parents or educators) to increase awareness and offer skills and support to families of people with substance use disorder. White says her main message when educating others about substance use is: “(Addiction) can happen to anyone. Treating people who use drugs with compassion and empathy goes a long way.”

When asked about the biggest barrier to care for people who use substances, both Moreland and White responded without hesitation: Stigma. People who use substances “don’t want to go to the hospital to talk to somebody about getting treatment because they get treated so poorly in general,” says Moreland. “Stigma is coupled with a lack of compassion because we’ve been raised to believe that people who use drugs are bad and weak people, (but) they aren’t bad people; they’re forced to do bad things to support their habit.”

“(Addiction) can happen to anyone. Treating people who use drugs with compassion and empathy goes a long way.”

According to Moreland and White, the first step to addressing both the stigma associated with substance use and the increasingly toxic drug supply is decriminalization of simple drug possession for personal use – a move RNAO also advocates for (read more at the bottom of the page). “Decriminalization is an easy thing to do because it’ll decrease stigma and it’ll shift the funds (from criminal charges) from the criminal justice system to health care, and treat people who use substances as a health matter and not a criminal justice matter,” says White. The shifted funds could go towards prevention strategies such as education and housing, as well as health and human resources, treatment, and updated research to support people who use substances and mitigate risks.

NP Marysia (Mish) Waraksa, clinical lead at Parkdale Queen West Community Health Centre’s safer opioid supply (SOS) program in Toronto, has worked with people who use substances since she was a teenager. She believes that decriminalization would have both a systematic and direct effect on opioid-related deaths. “People who are released from being hospitalized or incarcerated and go to use again are at the highest risk of overdose because they can no longer tolerate the same doses,” explains Waraksa. “Decreasing how much time people are spending in prison decreases overdose. It’s a ripple effect.” Waraksa also stresses that it should “absolutely not be the case” that individuals risk overdose after being in contact with the health system, but unfortunately it is the case given their decreased tolerance after discharge.

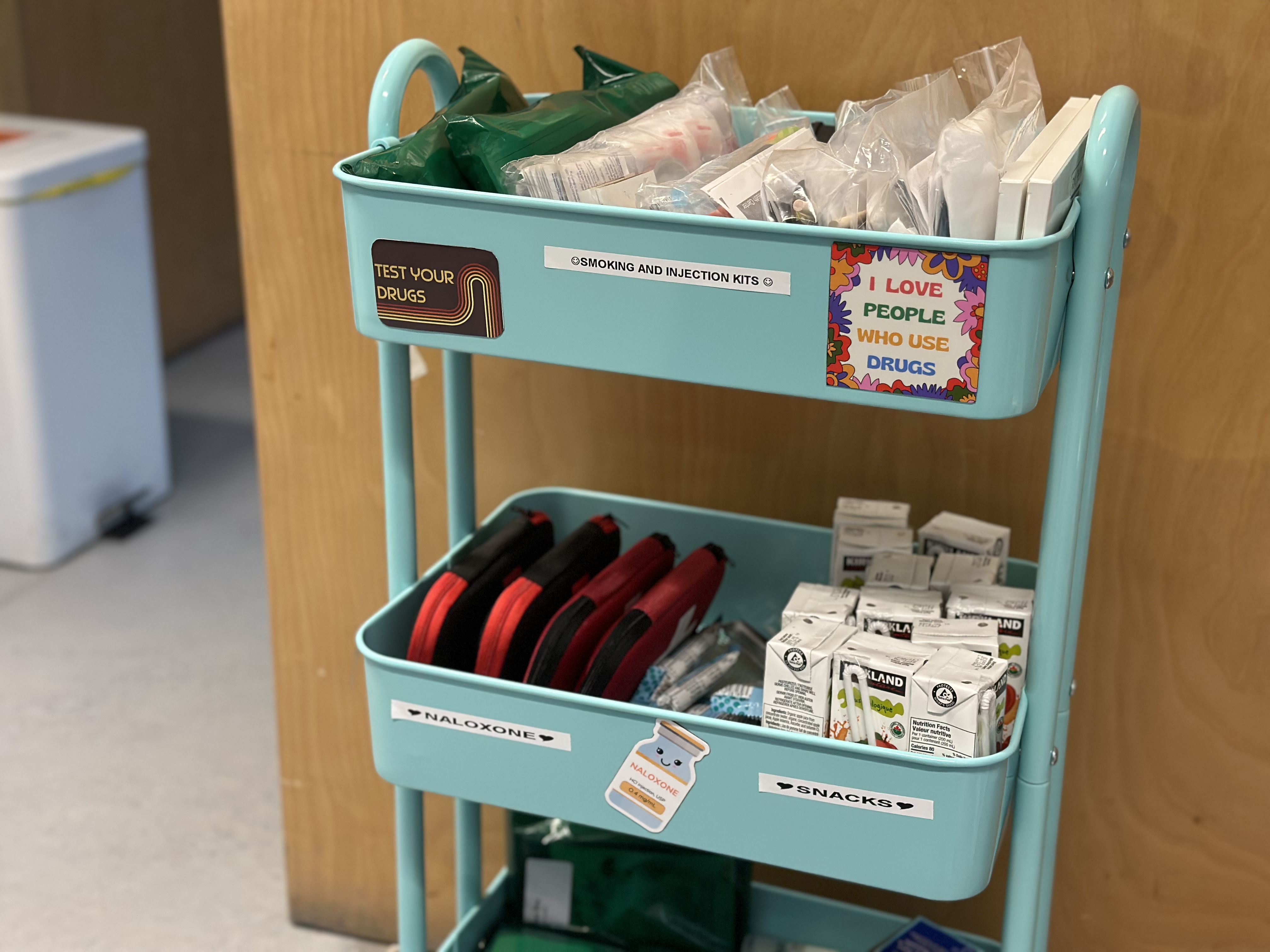

At the SOS program, Waraksa also provides her clients with primary care, safer supply – including opioid agonist therapy (OAT), prescribed methadone, suboxone, slow-release morphine and immediate-release hydromorphone – and drug testing, and also supports prescribers outside of the program. The program’s goal is to reduce overdose-related deaths and health complications caused by substance use, which has become more difficult given the increasingly toxic and potent drug supply. For example, because heroin has a much longer half-life (that is, the time for the amount of a drug's active substance in one’s body to reduce by half) than fentanyl, Waraksa notes that people who use fentanyl are injecting or using more frequently – often eight to 10 times per day – and "each time, there is an increased risk of infection and overdose."

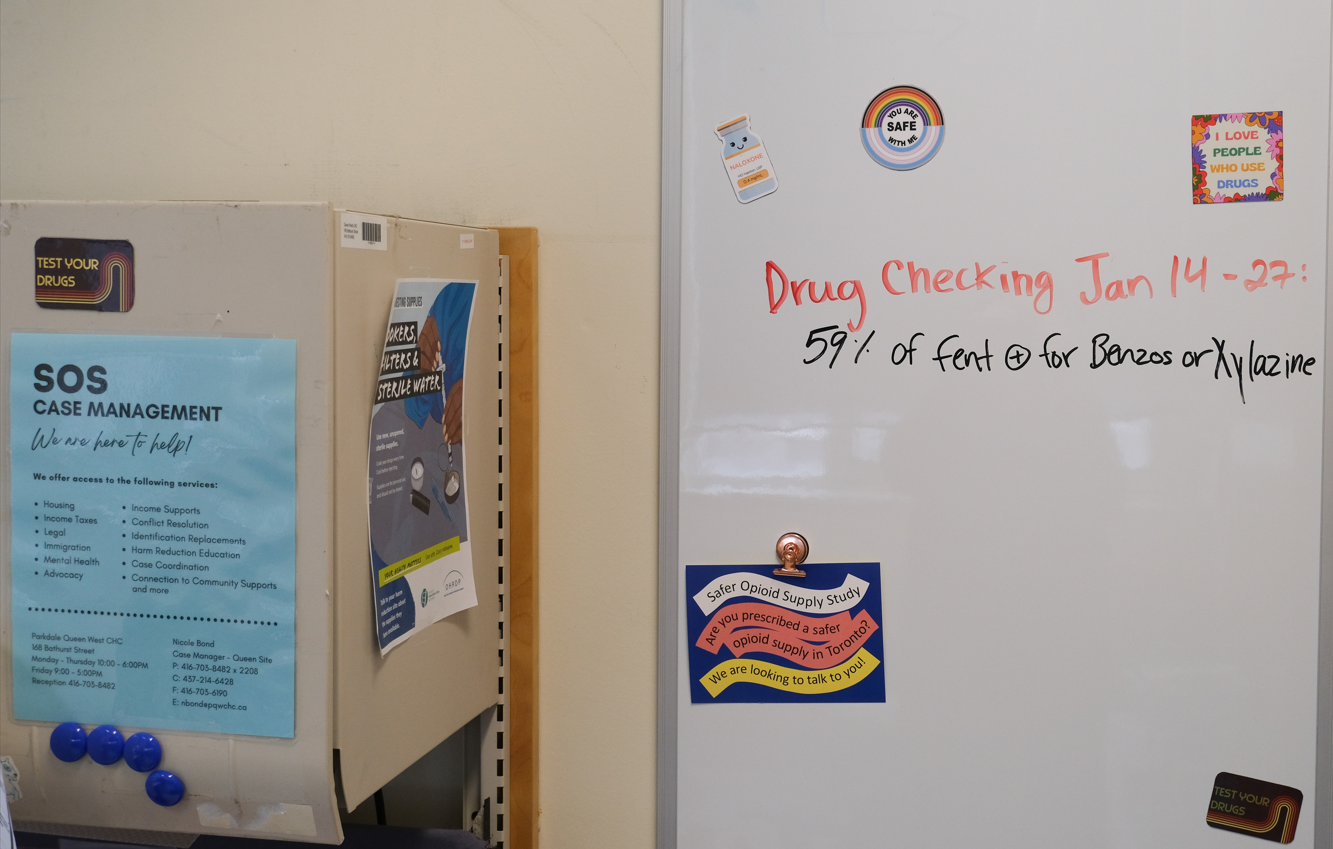

According to Waraksa, roughly 30 to 40 per cent of the drug samples submitted to Toronto’s drug checking services contain benzothiazolines (benzos), but benzos aren’t reversible with naloxone, thus further increasing the risk of overdose and complications. The drug supply became more toxic during the COVID-19 pandemic because she says “the closure of borders actually meant less smuggling into the country…which means there’s less fentanyl, so diluting it with other psychoactive agents like benzos possibly helped to stretch the supply and keep the profit margin high. All of these efforts are of course facilitated by the criminalization of drugs because there is no regulation of the market.”

The lack of regulation and ever-changing drug supply means it’s crucial for health professionals to prioritize their clients’ voices to ensure they’re meeting their needs – whether that means tapering down substances, providing information or connecting them with community supports – and using resources appropriately, says Waraksa.

In addition to safer supply, Waraksa says “we’ve created an environment where people are forging more trusting relationships with health-care providers after being alienated from our health-care system and having had pretty negative interactions in the past.” The stigma associated with substance use often results in the need to rebuild trust to improve individuals’ engagement with their health care. It’s also crucial for all health professionals to adopt a harm reduction approach to care to ensure consistency across all sectors and settings of health care.

“Harm reduction simply fits with the ethical standards and values of nursing care,” says Waraksa. Nurses “can promote a cultural change within the health-care system and hopefully successfully change other providers’ perspectives.”

To NP Émilie Frenette, supervisor of Toronto Public Health’s The Works injectable OAT harm reduction program, harm reduction is “one of the best care philosophies there is” that keeps the person at the centre of care. “It is not my place to judge or withhold care from folks who use substances,” says Frenette. “My role is to make sure they have the best information to make safer decisions while reaching their own health and life goals. This works better than telling people what they should do instead of listening to what they want.”

“Harm reduction simply fits with the ethical standards and values of nursing care.”

At The Works, Frenette provides clients with some primary care and supervises them as they inject opioids to replace their need to access the toxic drug supply often in addition to traditional OAT. Frenette explains there is a ritual attached to the act of injecting, so “having access to clean needles in a very open, non-judgmental and non-criminalized way saves lives” and she is there to give clients “the tools they need and be there beside them as they make their choices.”

Despite being in a different health-care setting, NP Paul Tylliros has a similar approach to the virtual primary care he provides at Waasegiizhig Nanaandawe’iyewigamig in Kenora. Like Frenette, Tylliros promotes holistic care that keeps the person at the centre and prioritizes “biography before biology.” During visits, he asks “What is the individual about? Who are they? What’s their lived experience?” to establish therapeutic relationships with his clients. “Health outcomes improve because there is engagement, whereas there was never engagement before,” says Tylliros. “There are thought-provoking discussions that lead clients from asking ‘Who are you and why would I trust you?’ to thinking ‘I can do this; I can try this.’ Individuals do make change when they’ve been given the opportunity to be treated like an individual first.”

Tylliros credits his work with Indigenous communities for leading him to view health care through a wholistic lens. In Indigenous communities “all of the pieces of the puzzle are equally valued – mental health and addiction services, nursing services, crisis-intervention – so they all work together.”

That’s why Tylliros says Ontario needs to take an upstream and preventative systems approach to effectively address the overdose crisis: “we have to look at all levels and the continuum of health care because (people with substance use disorder) are accessing health care at different points…(so) we need to provide equal opportunity for everybody.”

That’s why harm reduction is prioritized at Sudbury’s Health Sciences North. The hospital operates using a philosophy of harm reduction that extends across all of its units and outpatient programs. RN Michael Roach, regional lead for addictions services, helped to develop the philosophy and says, “there are lots of specific actionable items that need to be done, but I do truly think there’s a need for a widespread culture shift… It’s about treating individuals who use substances with respect and building that trusting relationship with them.”

Ending the opioid overdose crisis won’t happen overnight, but nurses across the province are working day-in and day-out to advocate for policy changes, remove barriers to care, educate others on harm reduction, rebuild trust with people who use substances and ultimately save lives.

“It’s not something that’s easily fixed,” says Roach. “Recognizing that this is a human being that has likely gone through quite a bit of trauma in their life and changing the way we approach clients is really what it's all about.”

RNAO pushes the agenda to address the opioid overdose crisis

Alongside its members, RNAO is committed to increasing awareness and demanding action to end Ontario’s growing opioid-related public health crisis. Through various evidence-based initiatives, political advocacy efforts and educational resources, RNAO is raising the profile on the immediate need for change grounded in harm reduction.

Letter in support of drug checking services

RNAO signed RN Hayley Thompson’s January 2023 letter in support of increasing Toronto drug checking services. These services at supervised consumption sites promote harm reduction and are needed given the toxic drug supply.

#DecriminalizeNow

In October 2022, RNAO announced its #DecriminalizeNow campaign to encourage mayoral candidates in municipal elections in communities across Ontario to pledge support of decriminalization of simple drug possession – a federal exemption of Section 56.1 of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.

In the media release about the campaign, RNAO President Dr. Claudette Holloway said “Nurses have been sounding the alarm on this preventable health crisis and offering evidence-based substance use policy since before the pandemic, yet we have continued to see the number of deaths, hospitalizations and emergency visits soar due to limited or no direct services and supports and an increasingly toxic drug supply. Through this campaign, we are urging mayoral candidates to confront the impacts of the overdose crisis in their cities and to take action upon election.”

Continued criminalization of drug possession stigmatizes substance use and people who use certain substances. This stigma creates barriers to health care and forces people to use alone – factors that increase the risk of death from overdose. The campaign attracted media interest, increasing public awareness on the crisis. Read RNAO’s fact sheet to learn more about the opioid overdose crisis.

Opioid overdose crisis issue page

In the policy section of RNAO’s website, there is an issue page dedicated to the opioid overdose crisis. The page features information, policy documents and ways for visitors to become familiar with the crisis. The web page also features RNAO’s Action Alert calling on the provincial government to end the overdose crisis. Sign and share the Action Alert.

Webinars

RNAO regularly hosts webinars related to harm reduction and the opioid overdose crisis, including “Nurses in harm reduction: The need is now!”, as well as "Harm reduction: Expanding beyond the decriminalization conversation”.

Engaging Clients Who Use Substances best practice guideline

Released in 2015, this guideline provides evidence-based recommendations for nurses and other members of the interprofessional team across all care settings who are assessing and providing interventions to individuals who use substances or with substance use disorder.